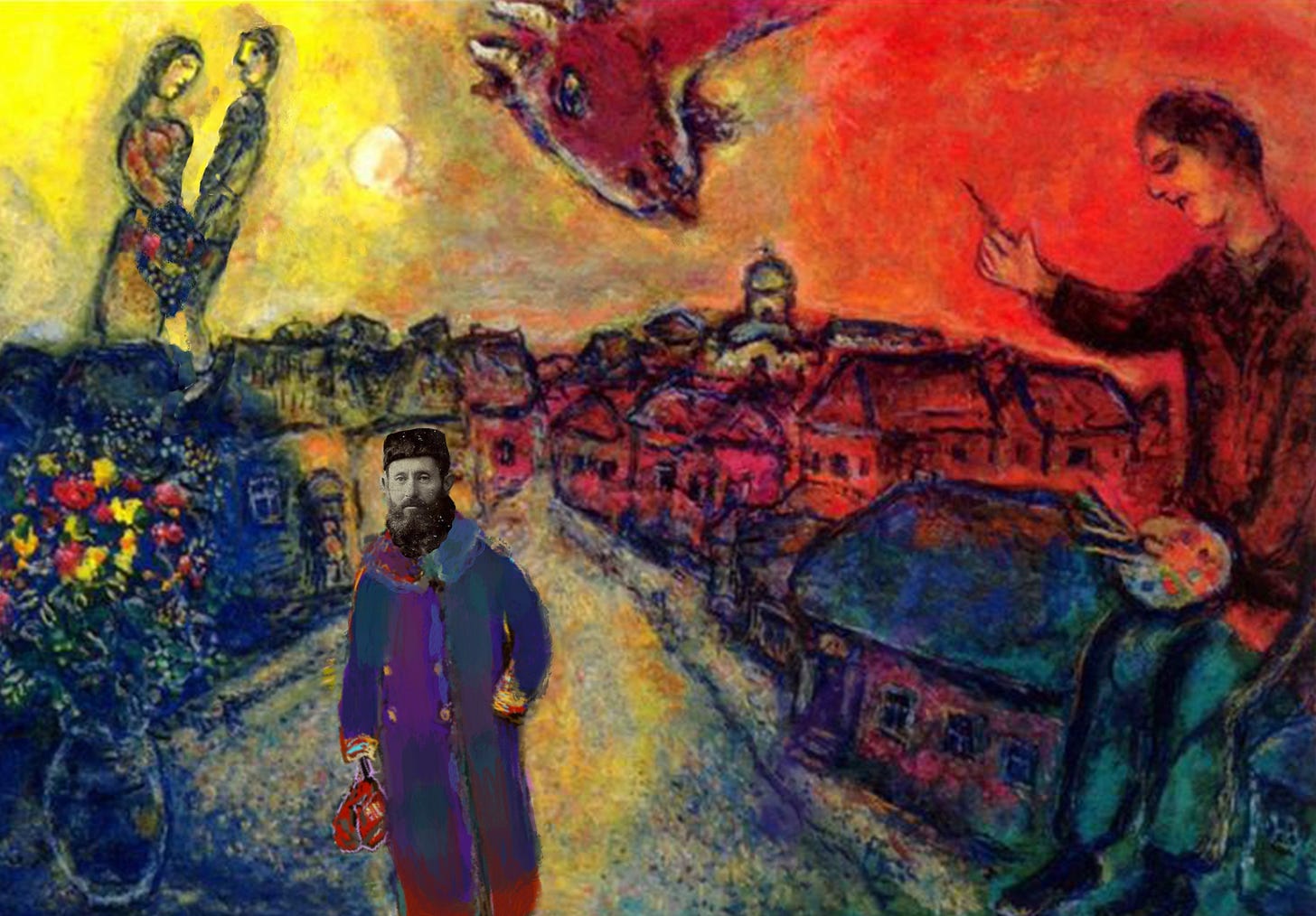

✨ Marc Chagall & The Rebbe: How Chabad Chasidic Thought Inspired Jewish Art

Chai Society Season III Episode 2

This installment of the #ChaiSociety Dispatch is a look at the intersection of Chasidic thought and art. Did the Chasidic movement influence modern Jewish art - and what lessons can we lean for our own lives?

This email comes on the eve of Passover. It also coincides with 2 Nissan, the yahrzeit of the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom Dovber Schneersohn, who figures deeply in this story.

Please share your thoughts and insights in the comments, and be sure to check out the exciting events we have at the end of the article!

Close your eyes for a moment and picture the shtetl - the timeless home of Eastern European Jewry. What do you see? Small homes with bright colors? Bearded chasidim in hats and coats running in the snow? Chickens and goats? Perhaps a chupa in the air or a fiddler on the roof?

No figure has had greater influence on not only Jewish art (at least in the its modern, Ashkenazi sense) but also the lens through which many Jews see their own past, than Marc Chagall.

Born to a Chabad Chasidic family in Vitebsk in 1887, Chagall was part of a proliferation of Jewish artists in the region at the time. His teacher, Yehuda Pen, was also from a chasidic family. S. An-sky, author the play the Dybuk and a famed Jewish ethnographer, came from a town rich in Chasidic history and Chagall's own wife Bella Rosenfeld was raised in a Chabad home.

This cohort of Jews grew up in rapidly secularizing homes, yet they yearned for a sense of Jewish authenticity to share on world stage.

As El Lissitzky writes1, in describing his trip to the ancient synagogue in Mogilev on an ethnographic expedition for S. An-sky, “Cohorts of heder students, at a generation’s remove from Gemara learning, had nevertheless been steeped in the bitterness of analysis.”

“And so we, having only just taken a pencil and a brush in hand, began quickly to anatomize not only nature around us, but also ourselves. Just who are we? What place do we hold among the nations? And what is our culture as such? And how exactly should our art be? …

Seeking around for ourselves, for the face of our time, we tried looking into the old mirrors, in order to ground ourselves in the so-called “folkways.” In the beginning of this era, almost all peoples had taken this path.”

Reflecting in these “old mirrors” these young artists shared a reflection of the innate chasidic appreciation for the beauty of heartfelt Jewish observance performed by simple, unlearned Jews, the sense that there is a prime, unifying force that runs through all of Creation, these core tenets of Chasidic belief trickled down to the artists.

Perhaps exemplifying the symphonic nature of chasidic belief in finding G-dliness everywhere is story Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, relates2 :

“One day in the summer of 5656 (1896), I was strolling with my father (the Rashab) in a field in the country resort of Bolivke, near Lubavitch. The crops were almost ripe; the grain and the grass rippled in a gentle breeze.

“Behold G‑dliness,” my father declared. “Every movement of each single ear of grain and blade of grass was included in the Primordial Thought at the very outset of Crearion, He who watches and gazes until the end of all the generations. Divine providence causes this thought to be realized for the sake of a specific G‑dly intent.

G‑d’s providence governs every minute creation… a fallen leaf that has been tossed over and over by the wind… or a bit of straw which someone used when thatching a roof some years ago…. To move them from one place to another… a stormwind breaks out, shaking heaven and earth in the middle of a warm sunny day and brings to fulfillment the Divine providence that governs this small stray leaf and old wisp of straw.””

This is not to say the Chagall or his contemporaries were religiously observant - they struggled, rebelled and forged their own paths - nor did they have strong yeshivah educations - but the milieu they were raised was one permeated with Chasidic life.

Bella, in describing her youth, mentions portraits of the Alter Rebbe and the Tzemach Tzedek, the founder and third Rebbe of Chabad, respectively, on her wall3:

“The voices echo back from the windows, clamber up the walls, awaken the portrait of the old Rabbi Shneurson that has hung in our house for years. The rabbi looks down with his green eyes and listens to each voice as if he were testing everyone. On the other wall, the portrait of the aged Rabbi Mendele cannot remain quiet either. Pensive, wrapped in a white cloak, and with his long white beard, he comes down from the frame as though he had been called to the reading. The bare walls prick up their ears, the ceiling comes down, listening to the haggadah; it has to carry each word upward. Page after page, the words pour out like sand in the desert.

I am tired from looking at everyone. Where are we?”

Thus after meeting famed German-Jewish Impressionist Max Liebermann, Chagall quipped4 to this wife “that painters too are divided between "Misnagdim" and "Hasidim." Liebermann and his generation were Misnagdim in art. ‘But the new art among Jews began with Hasidim.”

Whatever little Chagall did know of the Chasidic world in terms of its core teachings and text, its deeper spiritual searching was communicated and felt by him.

An interesting anecdote can be found in Chagall’s autobiography.5

After their marriage, Chagall himself went to visit his grandparent’s shtetl, Liozhna, where the fifth Lubavither Rebbe, Rabbi Sholom Dovber, the Rashab, was spending the summer.

In the country where we spent the summer, lived the great Rabbi Schneersohn.

The inhabitants from all the region round about came to consult him. Each one with his troubles. Some wanted to get out of military service and came to ask his advice. Others, disappointed at not having children, implored his blessing. Some people, bewildered by passage in the Talmud, asked for explanations. Or else a they simply came to see him, to be near him. How do I know?

But certainly no artist had ever been registered on the list of his visitors.

My God! Bewildered, but at a loss to choose a place to live, I too ventured to ask advice of this scholarly rabbi (I remember the rabbi's songs my mother used to sing on Sabbath evenings)…

In summer, he lived in the country and his house reminded one of an old synagogue, surrounded by mezzanines, by annexes for his followers and his personnel.

On reception days his antechamber was full of people. They pushed and shoved each other amid a hubbub of noise and gossiping.

However, for a good tip you got in more easily. The porter gave me to understand that the rabbi did not converse with ordinary mortals. I must put everything in writing and hand him the note the moment I crossed the threshold. No explanations.

At last, my turn having come, the door was opened before me and, shoved by that ant heap of human beings, I find myself in a vast green drawing room.

Square, almost empty, silent.

At the far end, a long table littered with notes, sheets of paper, requests, prayers, money. The rabbi is the only one seated.

A candle flares. He skims through the note.

"So, you would like to go to Petrograd, my son? You think you will like it there. So be it, my son, I bless you. Go there."

"But, Rabbi," I say, "I'd rather stay in Vitebsk. You know, my parents and my wife's parents live there..." "Very well, my son, since you prefer Vitebsk, I bless you, go there."

I should like to have talked at greater length with him. So many questions were burning my tongue.

I wanted to talk about art in general and mine in particular. Perhaps he would instill into me a little of the divine spirit. Who knows? …

Without a backward glance I reached the door and went out. I ran to my wife. It was moonlight. The dogs barked. And there was nothing half so good as....

Since that time, whatever advice I am given, I do exactly the opposite. I could simply have stayed in that village where I would have blindly followed that same rabbi, who was returning to his headquarters in the little suburb of Lubavitch.

But the war intervened and my class was called up....

Had Chagall opened up to the Rashab about art, the conversation would have surprised him. The Rashab seems to have had a keen interest in art. He traveled to France for the first time in 1884. As the Rebbe, noted in a letter written on in 1969, the Rashab, despite being punctilious on how he spent every moment of his time, spent hours at the Louvre taking in the art.

In 1891, at his younger sister’s wedding, he recounted three of the paintings he saw in exquisite detail.

Art is created by means of both feeling and talent (chush v’kisharon) - and despite being two disparate human faculties, both complement each other in the creation of art.

“There are three ways to create an image,” the Rashab taught.6

“There is the mental image that is created through deep thought

Through speech one’s words can paint an image

Through the act of painting one can create a physical image.

These three forms of creating an image bring the image to life in three different ways.

The image in the realm of thought can brings the experience alive to the one thinking. The image in the world of speech can paint a mental image that now comes alive for others.

Through painting, the realm of action, image itself to comes to life.”

In doing so, the Rashab recounted a trip to a museum where he saw three paintings attributed to the famous artist Raphael. Each of the three paintings is described in exquisite detail. Describing the third painting, he said:

“The third painting depicts a Roman court in all of its particulars: The court jail where the prisoners are kept, bound in iron shackles, the hall of judges and their place of repose, those up for judgement standing while they await their fate, the witnesses, the prosecutor and defense, and the people gathered to hear the judgement rendered. Among the crowd stands family of the prisoner, who have fainted from the words of the prosecutor, in his quest to render a biting decision on the fate of the judged. A small child stands beseeching the judges, begging to say a few words on behalf of his father before he is sentenced to death. The child stands on a chair, his arms outstretched, his right arm points to the gathered crowd while his eyes stare at the judges, as if to say “You must know, judges, that you will need to give an account on High for every word you say” ... "

After describing this final painting the Rashab recounted, “I stood transfixed in front of this painting for a considerable amount of time, unable to move from my spot. When I finally did move, I needed to find a chair to rest in. I stayed there until the museum closed - revisiting that painting three times due to the strong impression it left on me.”

“There is a considerable amount seeing these paintings gave me in divine service,” he concluded “for we learned from the Baal Shem Tov that ‘everything a Jew sees and hears is a lesson and a path in serving G-d.’”

More so, the Rashab not only learned lessons from art, but used art itself as a tool for spiritual connection.

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn recalled7 how his father once visited a museum, “where spent an hour or two staring intently into a painting of the crossing the Red Sea, as tears flowed down his cheeks.”

“When I was there with Mr. Bernstein,” Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak recalls, “We tried to determine the reason for his tears. Our conclusion was that the soul, despite the fact that Above it can viscerally see G-dliness, it becomes more apparent through the descent into this physical world, so too this painting affected him, to viscerally see the splitting of the sea, and as result of the spiritual yearning he experienced by looking at this painting, tears flowed from his eyes.”8

One wonders what would have happened if Chagall had indeed followed the Rashab back to Lubavitch. At the time, the Rashab was in the midst of groundbreaking exploration of the depths of the divine, and while surely the unschooled Chagall would not have had the background to access these texts, who knows what unpacking them might have taught him?

There is, however, if not a direct comparison, a way to peer through the looking glass and glimpse at this parallel universe:

Hendel Lieberman was a chasidic artist. His art can be found in the collections of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, London's Tate Gallery.

His story - his struggles, growth and spiritual catharsis - will be continued in the next Chai Society Dispatch.

🏃 DO:

🎷 Join us on Thursday, March 18th for #openShabbat at SXSW as we bake challah, enjoy a special performance from Jazz legend Daniel Zamir, have great conversations and more!

🤝 Sell your Chametz online! It’s a super easy way to prep for Passover.

🍪 Get your Seder in a Box or pick up some locally sourced hand made shmurah matzah! Orders are now open!

🍷 Get a seat at the table! Join us for the Tech Tribe seder with the Lightstone family in our socially distant Tech Tribe HQ backyard space!

Chai Society is an exclusive email, sent throughout the year, by Tech Tribe just for you!

Like what you saw? Want more? Please feel free to forward this email far and wide!

Support Tech Tribe in our mission to empower Jews in Tech and Digital Media to explore their Jewish identities.

Follow us on Social: Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

Does your company do employee matching? We’re now listed on Benevity and Bright Funds!

Tech Tribe is an affiliate of Chabad Young Professionals

Tax ID 82-2619676

Born Eliezer Lissitzky near Smolensk, (1890-1941) Text from On the Mogilev Shul: Recollections, translation by Madeleine Cohen

Likkutei Dibburim, Vol. I, p. 168-170;

Marc Chagall and His Times, p. 358

Igros Kodesh, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Schneerson Vol. III p. 389

Sefer Hasichot 5698 p 271.

See also Reshimat Devarim, R’ Yehudah Chitrik p. 165 - who recounts who at another point, the Rashab took one of his chasidim to a museum, where they looked at portraits of famous European nobles and generals. The Rashab recounted not just the personal history of each leader, but which negative spiritual forces he personified.

LOL

"So, you would like to go to Petrograd, my son? You think you will like it there. So be it, my son, I bless you. Go there."

"But, Rabbi," I say, "I'd rather stay in Vitebsk. You know, my parents and my wife's parents live there..." "Very well, my son, since you prefer Vitebsk, I bless you, go there."