This month’s #ChaiSociety Dispatch takes a look at the power of song in Chasidic tradition. Don’t forget to check out upcoming events and more after the story!

“If words are the pen of the heart,” taught Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, “then song is the pen of the soul.”

How can you capture the ineffable? How can we convey the most sublime?

Words can express complexities - they give shape and form to the thoughts in our mind. They give heft and weight and expression to the abstract. But in that process of revelation, we also create constraints.

When we define a concept with one set of letters, setting graphite to paper and give body to prose, we lose the myriad other ways that concept can be expressed.

Look into the heart of a churning sea and describe it. Is it blue? Aquamarine? Purple or black? Once you’ve described it, you’ve captured it. And boxed it in.

But song flies high. Song, especially the wordless tune, can give expressions to the soul of the subject at hand.

Which is why music finds such powerful expression in our human experiences of the transcendent.

A beautiful piece of music can transport us. It can lift us on a sea of sound and raise us beyond our earthly limits.

Thus in the Temple of Solomon, the service of the Priests was accompanied with song.

So too in the nascent Chasidic movement, song took a central role in divine service.

In the Eighteenth century, when Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad, was asked by the sages of Shklov, in Belarus, to defend a teaching of his, about the power of song to draw the soul, he gave those gathered two options.

He could try to constrain the sublime concepts he wished to express, boxing the ideas into words that could then be conveyed - verbal answers for each question and each questioner . . .

Or he could sing a single niggun, a wordless melody, that would address all of them at once.

And so Rabbi Schneur Zalman sang. Every person in the room felt himself transported from the crowded hall to the innermost recesses of the mind, where one is alone with the confusion of thoughts, alone with questions and doubts. Through song, the confusion was dispelled, the doubts resolved. By the time Rabbi Schneur Zalman finished singing, all the questions in the room had been answered.

And so the tradition of song, unbounded expression of the soul, continued.

The intangible spiritual nuances that could only be conveyed by hearing the music, remained.

Yechiel Halpern was a grandson of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s students, but was raised outside the religious fold. A gifted singer, he was classically trained, and performed in the theaters and opera house of Kharkiv, Ukraine.

But something called within him, tugged at his soul, and drew him to explore the songs of his ancestors.

And so he traveled to the town of Lubavitch, some 500 miles away, and began to learn the art of the niggun. Looking to grasp at that light of the soul and capture the songs, he wrote down the notes of what he learned. He put graphite to paper and tried to transcribe the soul for others to see.

When his teacher, Rabbi Leib Hoffman of Chashnik, saw what he had done, Halpern’s attempt to constrain the ephemerality of music to the limitations of notes, he was rebuked. And so Halpern ripped up the papers.

The song was still free.

A song may be the expression of the soul. But what is a soul without a body to dwell in? What good is the pen if there is no paper on which to write?

And so, the work began to transcribe the songs.

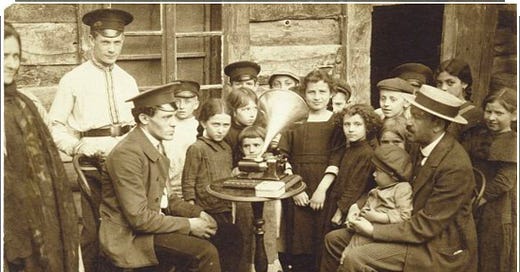

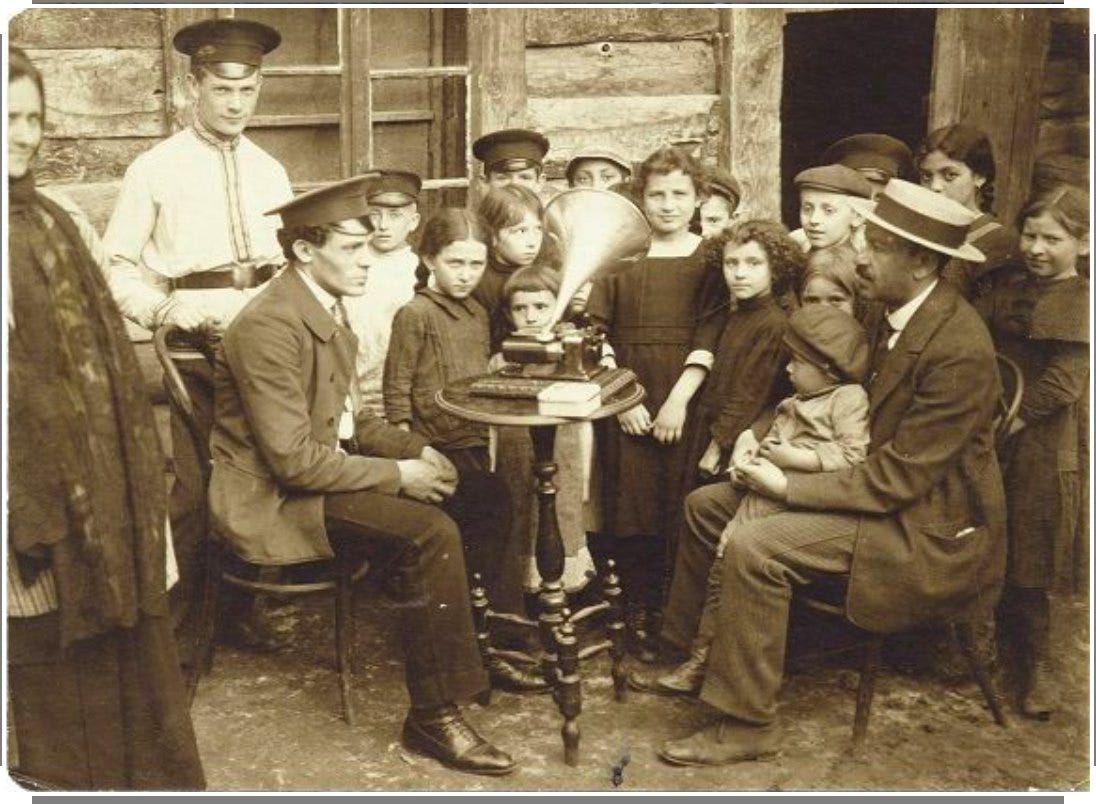

First it was in dribs and drabs. Ethnographers roamed the Pale, recording Chasidim in their element — Preserving songs on wax cylinders or in rushed notes.

But then came the First World War and the rise of the Soviet Union and the displacement of communities once confined to the Pale of Settlement across the expanse of what was once the Russian Empire, and beyond - to America, Israel, Australia, the four corners of the Earth.

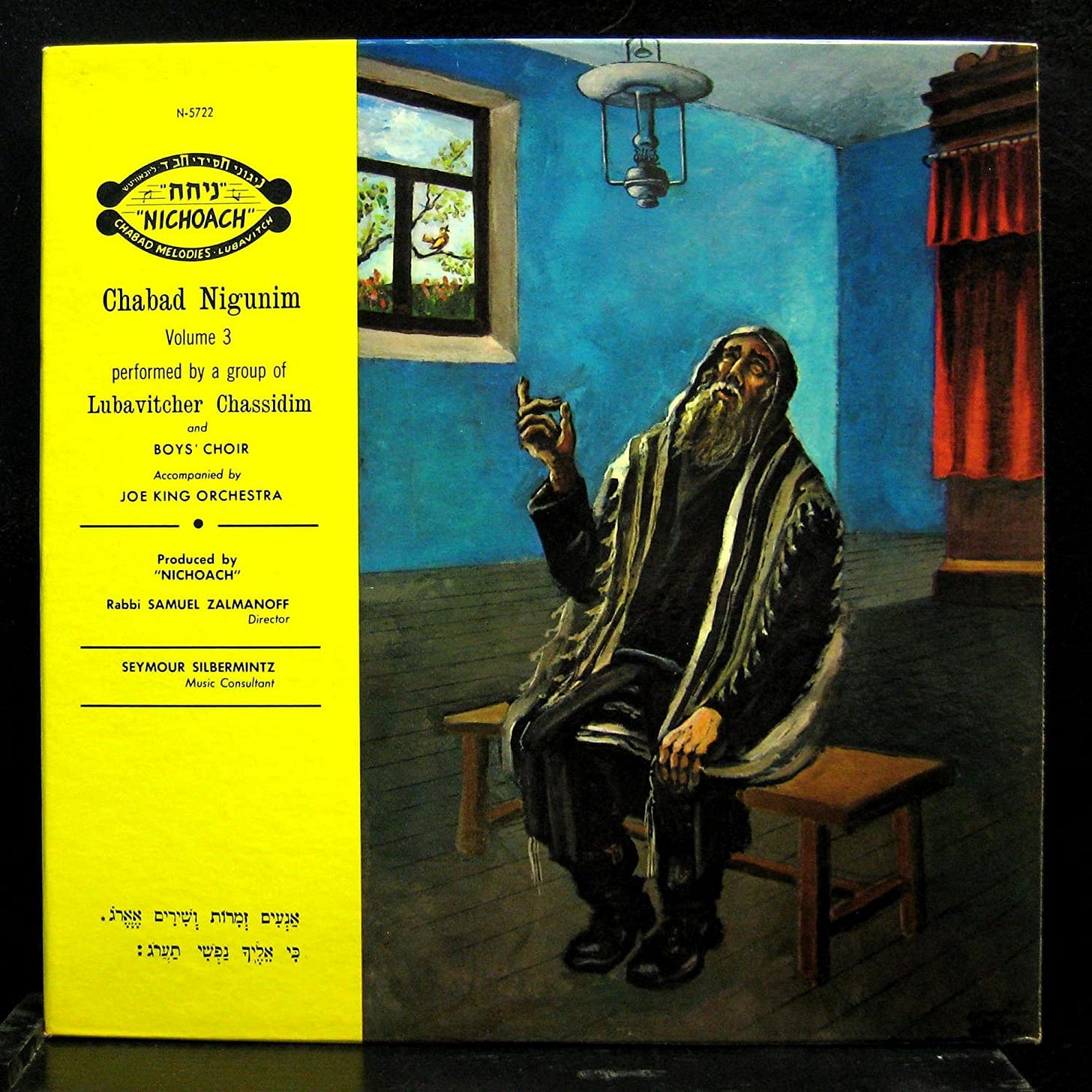

Rabbi Yosef Yitzhak Schneersohn of Lubavitch, realizing that to save the songs, he would need to transcribe them, established an organization to catalogue the repertoire of Chabad chasidic songs.

Writing to Yechiel Halpern, he gave permission for the chazan, stranded on the other side of the Iron Curtain, to write down the music he knew. But the resulting transcription couldn’t be read.

“Those musicians that play instruments see his notes and tell me they must be written for singers,” Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak lamented. “And those that sing tell me they must be arranged for instruments.”

The work continued, on paper, record and tape.

And today, confined as they are, they can be passed on. . .

So that when those who wish to sing may gather, they can continue to sing the songs, and write with the pen of the soul.

Hear a niggun performed by Shmuel Helperin (not related to Yechiel), 39, a shoykhet (Jewish ritual slaughterer), who heard this melody from Motl Shiroker, in Babinovichi, Belarus, [1910-1920’s] and recorded by Zinoviy Kiselgof

This story is edited from a version that will appear in Plumbago Magazine

📸 Pic:

🏃 DO:

🍔 Jewglers x Tech Tribe: Curated Conversations returns for all the MoTs at Google! Email for details about about our discussion on Is A Lab Grown Cheeseburger Kosher on May 26 at 12:30pm.

✨ Have you read last month’s #ChaiSociety Dispatch? Find out what we’re working on in Everything New Under The Sun

💬 We’re starting a new place for members of the #ChaiSociety to schmooze, network and chat.

Which would you prefer? A special Slack channel? Discord channel? Facebook Group?

Let us know by replying to this email or in the comments!

Chai Society is an exclusive email, sent throughout the year, by Tech Tribe just for you!

Like what you saw? Want more? Please feel free to forward this email far and wide!

Support Tech Tribe in our mission to empower Jews in Tech and Digital Media to explore their Jewish identities.